Researchers have developed a small, soft, flexible implant that relieves pain on demand and without the use of drugs. The first-of-its-kind device could provide a much-needed alternative to opioids and other highly addictive medications. It works by softly wrapping around nerves to deliver precise, targeted cooling, which numbs nerves and blocks pain signals to the brain. After the device is no longer needed, it naturally absorbs into the body — bypassing the need for surgical extraction.

All posts by keith

Bauhaus – Bela Lugosi’s Dead (Rez 毎日JUNGLIST Remix)

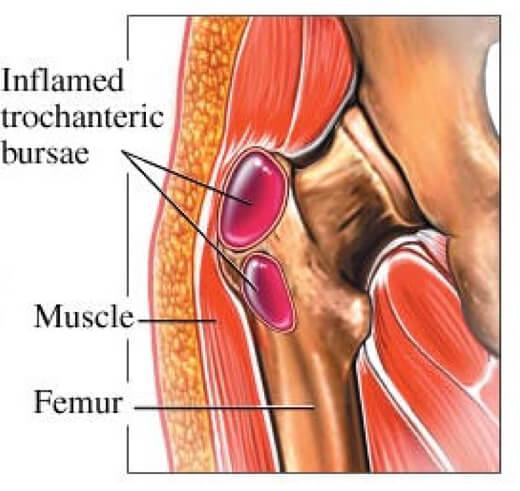

Hip Trochanteric Bursitis – A Runner’s Approach | Runnerclick

Like other large, mobile joints, the hip is more prone to overuse, injury, & other ailments, like hip bursitis. Find out more on the article!

Source: Hip Trochanteric Bursitis – A Runner’s Approach | Runnerclick

This is what I’ve got, with no MM involvement. It’s painful but getting better by itself, more or less. Need to be doing exercises for that hip, and a less inflammatory diet. ie. cut out sugar and carbs mostly. Which I should be doing anyways. I think it comes from the way I walk on that leg, because the knee isn’t quite right, and when I use the cane I actually put a lot of weight in that side.

Dedication’s what you need | John Self | The Critic Magazine

Down with the gratitude-bloat of authors’ endless lists of acknowledgements…

Source: Dedication’s what you need | John Self | The Critic Magazine

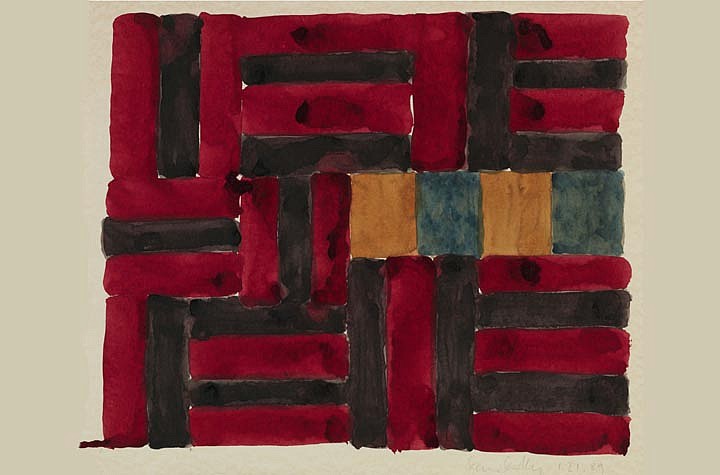

Sean Scully, Painter Poet by Donald Kuspit

I think the key to Scully’s art are the 13 etchings he made to accompany James Joyce’s Pomes Penyeach, 1993 and his 10 Etchings for Frederico Garcia Lorca, 2003, along with Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, which, as Scully said, “made a lasting impression on him.” Joyce and Beckett are Irish, as Scully is, and Lorca was Spanish. The homosexual and republican Lorca was a misfit in Franco’s fascist Spain; he was murdered by it. Joyce and Beckett were alienated from Irish society; Scully was what might be called a natural born alien and outsider in it because he was an Irish Traveler, “a traditionally peripatetic ethno-cultural group originating in Ireland,” sometimes mistaken for or confused with Gypsies, “generally found in Eastern Europe.” They are two distinct cultures and societies, with different languages. In 2011 there were around 29,500 Irish Travelers in the Irish Republic, and they are generally regarded as inferior whites, as the scholar Michal Wolniak notes, and as such marginalized, and perceived as “mad, primitive others,” as he writes. Sean Scully, born in Dublin, Ireland in 1945 to working class Irish Traveler family, could not help but have an inferiority complex.

Luxuriant Tufted Portraits by Artist Simone Saunders Exude Black Joy | Colossal

I celebrate the wins. I know the darkness in this world, so do you. It can drag us down. And when I post, positive messaging is key for me. To share light and love and to look at the world as vibrant and colourful as it can be….It’s reflected in my textiles, to uplift narratives often tethered to dark undertones, with the gift of bright hues. I’m not asking anyone to “smile”, because life will hurt. But hold onto your light… keep grasp of your love.

Samuel R. Delany’s Atlantis: Model 1924 and the Origins of Blackness

“Atlantis: Model 1924” belongs among the most important fiction in Samuel R. Delany’s vast bibliography, precisely because it distills so much of what makes this black, gay Harlemite science fiction writer such a unique figure in American letters—including his family’s history, his thinking on race, sexuality, and gender, his artistic methods as a writer, and his creative approach to literary criticism. “Atlantis: Model 1924” follows the life of a 17-year-old black kid named Sam on his journey from North Carolina to Harlem in the fall of 1923. The character is based on the author’s father, and the storyline is based on Delany’s family history. Two of the fictional Sam’s siblings — Elsie and Corey in the novella — are based upon the famous Delany sisters, Sarah (Sadie) Delany and A. Elizabeth (Bessie) Delany, who became internationally known centenarians with their bestselling book Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First 100 Years (1993).

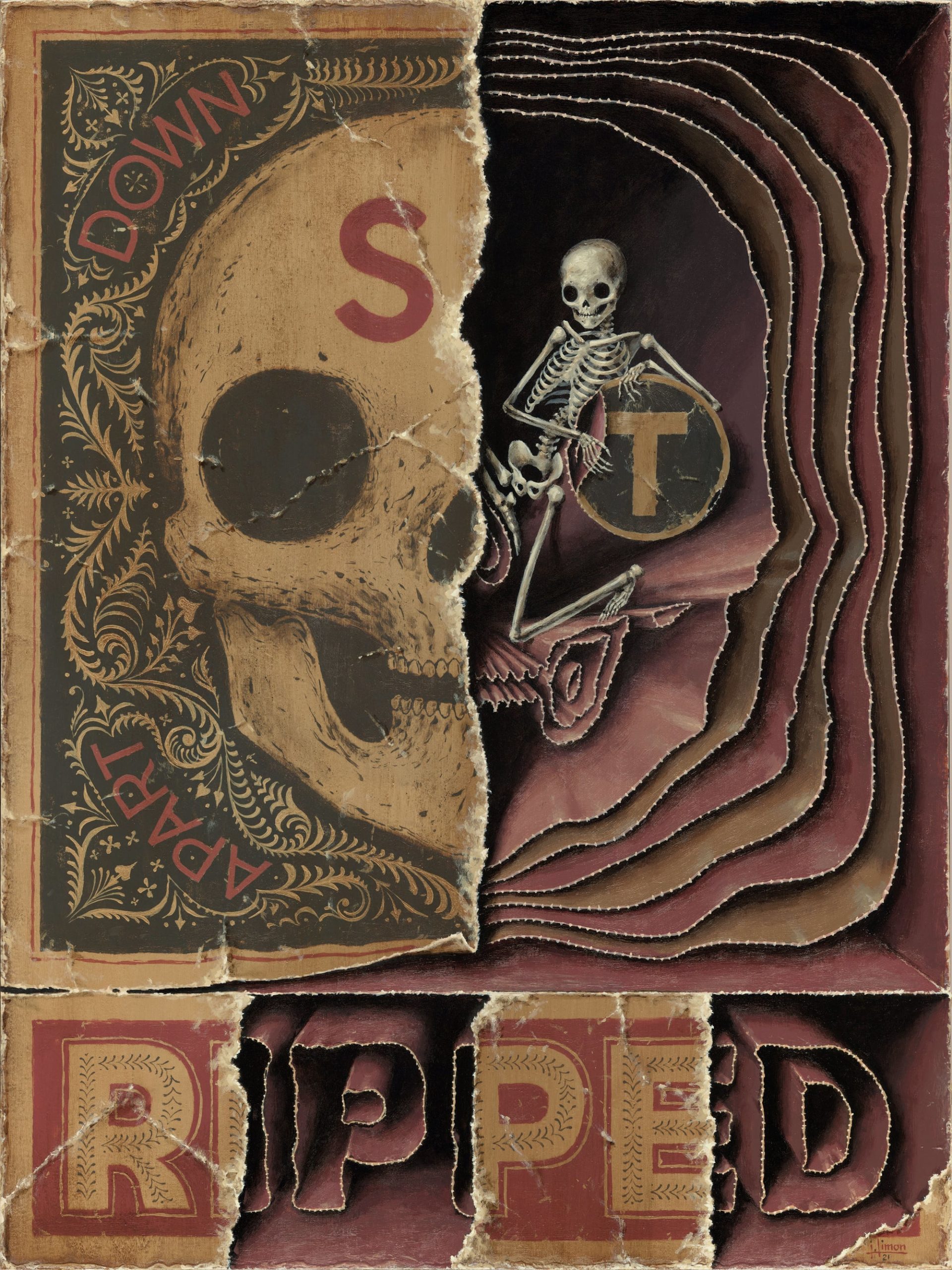

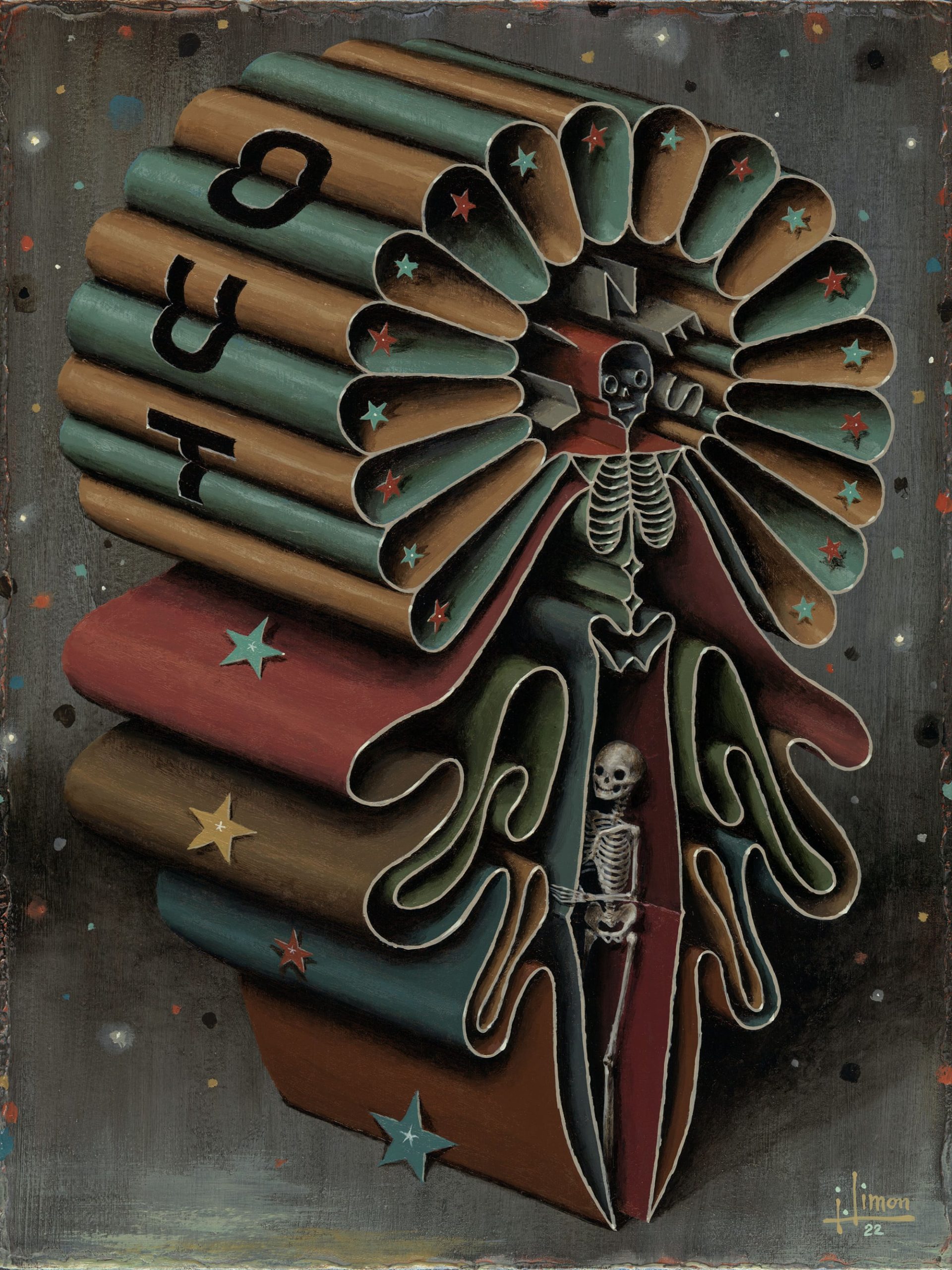

Paper Constructions Confine Skeletons to Uncanny Spaces in Jason Limon’s Paintings | Colossal

San Antonio-based artist Jason Limon (previously) conjures paper sculptures of 18th Century-style gowns, organs, and hollowed skulls with acrylic paint. The uncanny structures trap his recurring skeletal characters in cramped boxes and funhouse-esque constructions, where they attempt to disentangle themselves from their surroundings. Rendered in muted pigments, or what the artist calls “repressed tones,” the paintings utilize the anonymity and ubiquity of the bony figures to invoke emotional narratives. Limon explains:

New measurements from Northern Sweden show less methane emissions than feared — ScienceDaily

Some good news in the climate change narrative.

It is widely understood that thawing permafrost can lead to significant amounts of methane being released. However, new research shows that in some areas, this release of methane could be a tenth of the amount predicted from a thaw. A crucial, yet an open question is how much precipitation the future will bring.

Source: New measurements from Northern Sweden show less methane emissions than feared — ScienceDaily

Permafrost runs like a frozen belt of soil and sediment around Earth’s northern arctic and sub-arctic tundra. As permafrost thaws, microorganisms are able to break down thousands of years-old accumulations of organic matter. This process releases a number of greenhouse gases. One of the most critical gasses is methane; the same gas emitted by cattle whenever they burp and fart.

Because of this, scientists and public agencies have long feared methane emissions from permafrost to rise in step with global temperatures. But, in some places, it turns out that methane emissions are lower than once presumed.